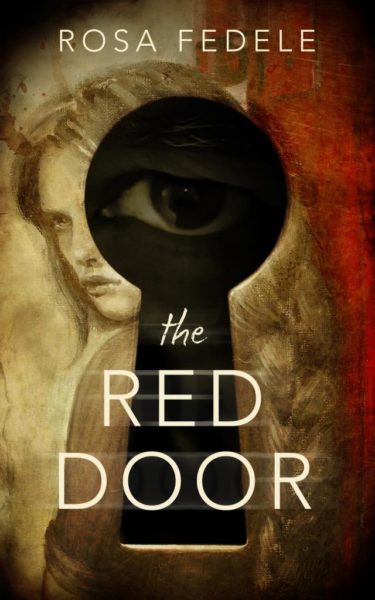

Another excerpt from THE RED DOOR in which we visit the notorious Kirkbride Block at Callan Park Hospital for the Insane.

The insane asylum, located in the grounds of Callan Park, an area on the shores of Iron Cove in the Sydney suburb of Lilyfield in Australia, was used for the housing and treatment of patients from 1878 until 1994. Famous inmates included Louisa Lawson, Australian suffragist, (mother of poet Henry Lawson) together with her sons, Charles and Peter; and (all my artist friends will love this!) J. F. Archibald, editor and publisher of The Bulletin and founder and namesake of the Australian Oscars of portrait painting, the Archibald Prize.

Trivia of the Day: A theft occurred in 2003 of thousands of medical antiques from the Callan Park Hospital for the Insane, including medical and dental instruments, lithographs and furniture, and a human skeleton!

PS Speaking of the Archibald, it’s that time of year again … please cross your fingers, toes and eyes for me and wish me luck! Photos will be released soon.

“Wearily, and with a sigh, he clipped the lens cap back on. The deluge was far too heavy and obscured any prospect.

He wouldn’t let the rain dampen his spirits, though. Dampen his spirits, he chortled. He still had it! Today he was feeling quite well, cheerful almost. Sometimes luck was on his side. Like the unexpected encounter two years ago when he was still a guest at the Callan Park Hospital – he remembered the day clearly.

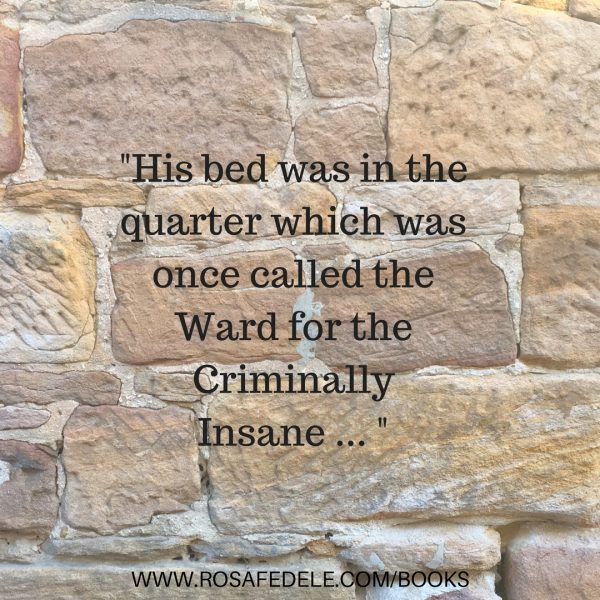

His bed was in the quarter which was once called the Ward for the Criminally Insane; in these more “enlightened” times it was simply known as Ward 18, and it could have been the closest ever to what he imagined hell might be, if such a place existed. The walls of the grand edifices which housed the institution, so venerable and elegant from the groomed lawns, contained a rotting society with the inevitable selection of brutes and sadists amongst both the misnamed “carers” and the wretched inmates. The hallways were rank with the essence of urine, misery and disinfectant, and tawny sandstone was imbued with the silenced screams of forsaken minds and tortured bodies.

The new patient’s arrival caused a stir amongst the populace; the rumour which preceded him was that he was a disturbed and violent murderer so, of course, everyone was eager to catch a glimpse. Muscled, tanned and blonde, the Nordic giant stood out like dogs’ nuts.

‘G’day Sven!’ He walked straight up and greeted the new resident with an audacious handshake on the first morning. The man refused to smile so, over the next few weeks, he began to entertain the surly and morose patient with stories about the staff and the other internees, often more for his own amusement, and to break the tedium, than for any other reason.

There was Bradley, the nurse; a thick, solid man with an ugly scar which disfigured his face from eyebrow to jaw. He had also once been a security officer at Maitland Gaol; his eye gouged out by a vengeful convict with a lethally sharpened toothbrush. During the day, Bradley was particularly good at joking with the patients, setting them at their ease and clapping them jovially on the back. When a fellow staff-member was feeling particularly low, he would pop out his glass eye and waggle it about until he managed to winkle out a smile, or even a snicker. But at night, long after the cold and unforgiving fluorescents were extinguished, Bradley was also particularly good at ambushing troublesome patients and inflicting indignities and brutalities, evidence of which was never recorded in the Case Book.

He warned him about Charles, who had been a paediatrician, and always appeared so urbane and cultured. Charles was fond of discussing the works of Twain and Hemingway, and his eyes would light at the opportunity of discussing the poetry of Wilde with a new audience. Charles was also a self-mutilator and, whenever possible, would suddenly and gleefully re-open his wounds mid-conversation and proceed to flick his blood upon the newest, and unwary, victim.

He gave him the heads-up on Vanessa, the groundsman’s wife. She was known around the mens’ block as Vanessa-the-Undresser and she was always happy to accommodate “the lads” whenever they could stray away from the screws long enough to hightail it across to the Oriental Gardens. In his opinion, a hand-job from Vanessa was far more therapeutic than any chemical, medical or surgical procedure the custodial morons of the Callan Park facility could administer.

In the end, his persistence paid off and the, by then, not-so-new patient began to open up. He heard about the man’s early years, and how it was growing up in Malmö. About his adored wife, and the infant son he was yet to hold. He told him about how excited he was to build his own home, and showed him the plans and elevations he sketched up with crayon on butchers’ paper during the long, empty nights in the Kirkbride Block. He told him he hadn’t actually murdered anyone, although he’d come close. And he told him about the “whispering” which began to contaminate his mind like an insidious worm, gnawing and niggling, while he had been employed on a short-lived and disastrous renovation project not so long ago; a “whispering” which he had trouble ignoring, and which disturbed him still.

A tenuous and fragile comradeship between the two began to gradually form, and it made living at the Hospital just a little easier to bear.”

Grab your copy of THE RED DOOR at Amazon or iBooks, links below. Rx